<<back to publications<< …...................>> to Teach0logy.xyz>>

Why have hundreds of millions of dollars been spent on developing the common core math standards if most people had not really wanted them?

This link leads directly to the answer to the question posed in the title. However, the logic, which supports the answer, is presented in the seven pages below.

The table of content

II. Research in education only matters if it targets the ways of teaching.

III. Any reform happens only when there are people who want to make it happen.

Foreword

The radical reformation of the U.S. system of education started after the Russian Sputnik orbited the Earth. Since then every President claimed continuing the reform as the national priority. Hundreds of millions of dollars have been spent. Every decade (on average) the Congress considers a new bill to continue the reformation. Naturally, the world does not stay still and education has to catch up with the changes, but if we single out one parameter of a success - learning outcomes of students, even after fifty-ish years of reforms there is still a lot work to do.

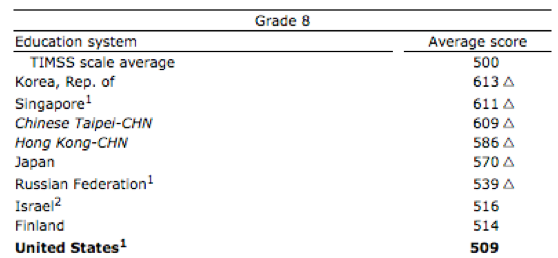

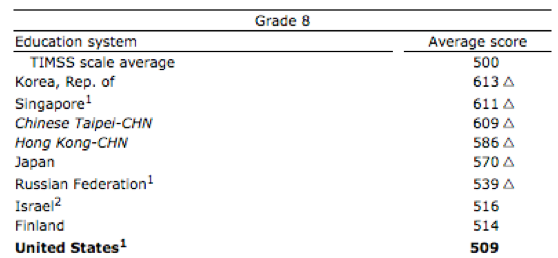

According to the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (nces.ed.gov/TIMSS; the picture below shows the results for 2011) the U.S. score is nine points above the world average, but U.S. is still behind Korea, China, and even Russia (which economy has been in shambles for decades).

Considering the fact that an annual U.S. educational budget is almost ten times greater then the Russia’s, we have to make a conclusion that the amount of money invested in education does not matter as much as the way it is spent (i.e. distributed). If we want to avoid another decade(s) of spending hundreds of millions of dollars and not seeing a significant improvement in learning outcomes of students, we need to analyze the reasons for not having a significant improvement in the past.

I. If we want to improve the results of teaching, we have to change the way we invest in teacher preparation.

Remember an old joke?

A policeman approaches a drunken guy crawling around the side-road light and asks, “Sir, what are you doing?”. “I am looking for the keys to my home”, the guy says. “It should not be too hard to find them at such a bright place” says the policeman. “I didn’t loose them here, I lost them over there”, says the guy. “For the God’s sake, why are you looking for your keys here, then?”. “Because”, says the guy, “it is brighter here.”

Where have we been looking for the keys to the educational reform?

The list is long. Charter schools, early college high schools, new textbooks, new standards, bringing tablets in classrooms, providing high speed internet, just to name a few.

Of course, the infrastructure matters a lot. But textbooks, or tablets do not teach students, teachers do. If the percentage of good teachers does not increase, nothing will help to increase learning outcomes of students nationwide. New schools will just affect the distribution of teachers between schools. New textbooks will not be used effectively by inefficient teachers. The # 1 investment (maybe not by the volume but by the priority) should not be an investment into infrastructure but in teacher preparation. This kind of investment currently is also vast and systematic, no doubt. The quality of teaching, however, remains to be not as good as everyone wants (report after report is criticizing the quality of teaching – for decades). Two questions immediately come to mind: why, and what to do about it?

Let’s use an analogy again (the joke above was an analogy, too).

A space shuttle really looks like an airplane. However, it is impossible to invent and to construct a space shuttle just by making airplanes better, and better, and better. Even the very idea of a spacecraft (including a shuttle) cannot be derived from the ideas which had lead to the creation of airplanes. Scientists and engineers had to find an absolutely new principle to just start thinking about the possibility of getting off the Earth.

For making a drastic change in improving the quality of teaching we have to find today a new leading principle to guide the reform.

Here I want to repeat my statement I made in my essay “Teachology 99.9: Everything, people who care about education, should know about teaching (at http://teachology.xyz/Teachology99.htm)”:

“The key problem of contemporary education is not an insufficient teaching, it is an insufficient teacher preparation. Effective, productive, sufficient teacher preparation will result in effective, productive, sufficient teaching (assuming the economical issues are resolved)”.

This statement does not require any research. This statement is a postulate (a.c.a. an axiom).

All people reading this essay are deveined right now into two camps: the ones who accept this postulate as a postulate, and the other ones. There is nothing wrong with this divide, this is how any science works; the future will show who is right (if we accept this postulate and plan our actions on it and the actions lead to the “better world” the postulate becomes a law, otherwise, it will be replaced with a different one and eventually will be forgotten by everyone except historians).

Naturally, as the author of the postulate, I build on it all my future logic (and my current actions).

The first consequence from this postulate is a statement that the absence of effective, productive, sufficient teaching is the sign of the absence of effective, productive, sufficient teacher preparation. Which means, in turn, that the current system of teacher preparation does not work, or at least is very much ineffective (otherwise we would not have to have a debate on why for too many students learning outcomes are not as good as we want).

What should be done about it? How can we make a qualitative change in teacher preparation? My version of the answer to this questions sounds like this: “Hey, Teacher, I am the Union, here is money, use it to become better prepared! (but, please, keep in mind, if you fail, we will have to let you go)”.

Becoming a true teacher takes time and effort. Everyone who wants to become a good teacher has the right to demand the best available training. Everyone who wants to become a good teacher becomes a consumer of the teacher professional development system. I believe that individual teachers should be granted money which they can use on their own professional development. Money should not go directly to an individual teacher but offered through a teacher association (I think a union would be a good candidate for that). That association should be placing orders for various teacher preparation activities, keeping track of their effectiveness, but also keeping teachers accountable for the results. To advance the preparation of the current and future teachers we all need to start trusting them with the way they improve their work (trust, of course, should be balanced by verifying that the results of their work show an improvement). Instead of experimenting on teachers (will they learn something or not if we make them to do this and that?) universities (and other providers) should reach out to teachers and ask them what do teachers need to be developed (in exchange for the money the teachers have from the Union, which gets the money from the NSF or other sources), or market to teachers already developed solutions. Don’t we usually say that the best way to teach someone to take responsibilities is making that someone to be in charge? It is time for teachers to say: “Let us make in charge for our own professional growth”.

No doubts, a math teacher should take a course about teaching math, and a math course. But the math course for a math teacher has to be multi-dimensional; while learning math a teacher also should exercise in reflecting on how he or she learned it, so a teacher would know how the new math knowledge had been developed (produced, internalized, trained) in his or her own brain. This is the kind of a professional development course teachers should demand. (http://teachology.xyz/Teachology99.htm)

Keep in mind that until teachers become true customers on the teacher professional development market, they will be fed by many “professional development” activities which will not help them becoming better teachers (but will help the authors of the activities with publishing new results of their study on how to teach teachers).

II. Research in education only matters if it targets the ways of teaching.

Let's carry out a mental experiment. Let us assume, hypothetically, that we put together a group of the best in the world designers of car wheels and gave them everything they had asked for to do their job. Then we had separately formed a group of the best designers of car engines. And we had independently formed a group of the best car body designers. Etc., etc. All the groups finally had developed the best car wheels in the world, the best car engine in the world, the best auto body in the world, etc. Now, ask yourself, what would had happened if we tried to put all these best auto parts together? The obvious answer is - nothing! They would not match each other, they would not fit with each other.

The absolutely same situation is happening now within research in education. Someone writes a fine textbook for middle school students. Another person independently writes a collection of problems for high school students. A third person creates an electronic encyclopedia for students at the college level, etc., etc. Each didactic tool can be helpful for a certain group of students, but they do not match each other! Hence, they will not make a visible change in the overall results of teaching.

Why?

Learning is a long and complicated process. As any process it has stages and phases, which are based on sequences of learning actions like “reading a text of the problem”, “making a sketch”, “listening to a teacher”, “writing a question”, “observing data”, and many others. Each learning action takes a certain period of time (different for different types of students, by the way). An effective/efficient learning process obeys the certain timing. This means that an effective/efficient teaching process must obey the same timing. However, if you read papers on education, you will not find one which would discuss the timeframe of using a newly invented learning tool. Maybe this textbook or that collection of assignments is good on its own, but a teacher is just unable to fit those teaching tools in the existing timeframe of teaching. If a teacher would try to use all newly developed learning tools in his/her lessons, the whole learning process would be just broken. But using just a single new element will not make a big effect on learning outcomes of students (another postulate, a.c.a a common sense observation).

Instead of trying to decompose the learning process into individual “learning atoms” and time each of them to unveil the exact structure of a learning process, the main research effort is concentrated on creating more and more new but functionally disconnected teaching tools.

The main reason for this “crisis of variety” of educational instruments is that to this day there is no social force which main goal would have been “forcing” researches into cooperation; nowadays funds go to almost anyone who offers a new and existing initiative, but there is no one who tries to connect them together and direct toward a mutual goal.

Ask yourself, what factor united all scientists, engineers, generals and all the staff of Manhattan Project? If you said “The mutual goal”, it would not help much, because it would not be specific (too general). And such a goal as “Making a new highly destructive weapon” could pretty much separate people because people may have different ideas of “highly destructive weapon”. But, the goal “Making a U-bomb” made people united because this goal had an absolutely specific outcome – an atomic bomb - which “everybody” could see, touch, use - the measurable outcome.

Analogically, “Making a good education” or “Improving education” is not a uniting goal. But “Making a certain/specific educational environment” could be the one. The measure of achieving the goal would depend on the specificity of the goal, i.e. on the learning environment chosen to be created. A goal like that, when achieved, should lead to a visible impact on the system of education. It also should be replicable. It should be related to a learning process of a large entity of the system (my view is that the “specific learning environment” should be composed of a set of classes “vertical” within one school – for example, one class for each elementary/middle/high school level).

III. Any reform happens only when there are people who want to make it happen.

Please, answer the following question (and be honest to yourself): “Which social group has “improving learning outcomes of students” as the goal # 1 for every member of the group?”.

The goal # 1 for a politician is to be reelected. The goal # 1 for a school or district official is to have the contract resubmitted. The goal # 1 for a parent is to have a healthy child. The goal # 1 for a teacher is to keep his/her job.

Whether we like it or not, we all are governed by the instinct to survive – at first as a biological entity, and when this task is achieved as a social entity (check for example the “Maslow's pyramid”). Every biological system, including human beings, functions in such a way, which allows it to be alive as long as possible (exemptions are rare and do not represent a healthy subject). To be alive a biological system must utilize some resources like food, for example. Where can a biological system get food? Only from the outside of itself (it cannot eat itself and keep a long life). In the social world “outside” means from other people. But instead of taking an actual food or something else, we take money as the universal equivalent for goods.

When other people give us money, usually it is not a gift, usually they want something in exchange. So, the logical sequence is simple; to support our life we need resources; to get those resources we need money; to get money we need to give away to other people something they need from us.

In short: to support our life we need to be needed – we may agree or disagree on how strong is the influence that need has on our motives, but the existence of this need is undeniable (it makes us “social animals”).

To be needed is the strongest subconscious motive of our activities, which is imprinted deeply inside of our human nature. This motive governs 90 % of brain activities hidden from our consciences. Our brain (but not us) can “feel” if there is a risk of becoming “not needed” any more, and starts looking for any way to escape that kind of a risk – even if consciously we do not have any suspicions about what might be happening and what can it lead to. As the result (one of many) of this subconscious work, we prioritize doing what we are getting paid for placing it above doing something else (that is why a developed society must provide to majority of people time to do something not related to their survival, so an individual could use that time for helping his or her self-actualization).

In short: we do what we are getting paid for; and I mean - not what we are told we are paid for, but literally, what we are paid for by people who want something from us - as our brain sees it.

I understand that I described a very primitive model of human behavior. But this model is pretty much sufficient for our discussion of what should we do to reform the reform.

The first conclusion we should make is that people involved in education should be paid for the results of their work as educators; as well as people responsible for reforming education should be paid for the results of reforming it, i.e. when it gets reformed.

We - the people - want from our teachers, school principals, district and state officials high learning outcomes for our students. Hence, we have to pay them only for high results the students achieve (“the merit pay” comes to mind). Hence, in the first place, we need to know the results as accurate as possible. Hence, we have to talk about measurability of the learning outcomes.

This is a very hot topic. The biggest problem – as I see it – is that almost everyone who is involved in the discussion has a strong opinion (different from others’) what and how should be measured. We have again a huge variety of tools used in different states, districts, at different levels. Teachers, students, parents are overwhelmed just by the sheer volume of the tests. As the result, we see a strong resistance to even the idea of testing.

The solution is not getting rid of testing, but making testing reasonable. The very first and the hardest thing to do is to change the approach to the development of testing materials.

I am certain that a tool and a procedure used to measure learning outcomes of students (taking any STEM course) must satisfy the following conditions:

(a) Every aspect of the development and the use of the tool has to be open to public and be able to be examined by anyone.

(b) The use of the tool must lead to gradable information on student’s skills and knowledge.

(c) The use of the tool must lead to gradable information on student’s skills and knowledge AND must not depend on any specific features of teaching or learning process.

(d) The use of the tool must lead to gradable information on student’s skills and knowledge and must not depend on any specific features of teaching or learning process AND must allow to compare on a uniform basis the learning outcomes of any and all students using the tool.

(e) Any institution adopting the tool becomes an active member of the community and can propose possible alternations to the tool to accommodate changes in the understanding of what students should know and be able to do.

It might seem impossible to develop measuring tool, which satisfy these conditions. But it actually can be done (follow http://teachology.xyz/mp.htm for more on this topic).

Officials at the federal or state or even district level should not use their own measuring tools, but should rely on the same system of collecting data on learning outcomes of students used by a school. Quizzes, tests, exams a teacher uses during a year and at the end of a year should be sufficient to make a conclusion on the quality of teaching. Development of such a system should be an immediate goal of the Government.

Let’s assume the new system to measure learning outcomes of students is in place.

Should we start using it to differentiate teachers’ pay?

No! (I know that perilously it sounded like I would say “Yes”, but it just to trick you into thinking it :)

The survival instinct is so strong that the most expected outcomes of a direct connection between the teacher's wage and the learning outcomes of students are (a) none – if a teacher is sufficient and cares about students and work on his or her professional growth independent of the external factors (teachers who are already good might get some raise, but that will not increase the number of good teachers); (b) increasing numbers of teachers leaving schools (either because they are not good, or because they do not want to be the object of tight scrutiny, especially if the officials are not very good at managing teachers) ; (c) faking good results to cover poor ones (just recall all the movies where a bad guy from the CIA wants to blow up civilians pretending terrorists would did it only because the government wants to cut the budget – the similar idea of faking things to keep to be needed).

In short: the merit pay will not affect weak teachers the way we want.

The idea of the merit pay is based on the assumption that the strongest motive to do a good work is the fear of being fired. But this assumption is wrong. Hence, the statement I made above that “we have to pay them only for high results they achieve” is wrong (the word “only” makes it wrong; and I did it on purpose). Yes: “we need to be needed”. We want to be needed. But humans are social beings, and “to be needed” for us is more than just “being paid”, it is “being accepted as a professional”, it is “being respected as a teacher”.

Let’s assume the new system to measure learning outcomes of students is in place.

The next step is making all the results open and available to anyone.

“I am a teacher, and anyone in the world can see how my students performed last year, and how my students perform now. But I should be paid the same wage as another teacher who teaches the same subject, at the same level, the same amount of hours, to the same number of students. I also know, though, that if another person can do my job better than I, I can be easily replaced. That is why I always want to learn how to do my job better. That is why I need extra money so I could buy for myself a good professional development course”.

A teacher has to become the central force for reforming the reform.

Researchers, officials, politicians are not really interested in significant improvement of the system of education (at least, directly). “We need to be needed” – remember? Imagine unimaginable; every school is perfect, every teacher is a top notch professional. In this scenario many people would not be needed any more. Subconsciously we know that for many of us constant reformation is much more “profitable” than the finished reform (“profit”, of course, means more than just money, it is also a respect, fame, recognizability, power, …).

That is one of many possible reasons for us to see new standards written every several years.

The latest incarnation of the standards is “The Common Core Standards” (CCS) developed by “The Common Core State Standard Initiative” (http://www.corestandards.org/).

I make a claim that the hundreds of millions of dollars spent on the development of CCS for mathematics is mostly a waste of money. That part of math we want our students to know has not changed for at least decades (if not for centuries). The stages of learning math also have been known for decades and cannot be changed more than by a little: you cannot teach quadratic equations right after finishing teaching addition within a hundred – it would be waste of time. Hence, if you place on a table the new common core standards and the one they replace, and compare them side-by-side, the difference in the content of math students have to learn will not be more than several percent (I think no more than 7-8 %). A closer look could show some rearrangement in topics or their goals; some of the rearrangements do not make much of a difference, some of the rearrangements do not make much of a sense (for thousands of years the natural way of science discover has been from less abstract to more abstract, from less visual to more visual, from less complex, to more complex, but – for different reasons – curricula developers do not always follow this path). Developers claim that new standards will develop students' thinking abilities. This claim has no scientific evidence to be based on, and more importantly, no one can and so far event wants to measure “thinking abilities” of students.

I am confident that if any math common core curriculum proponent would challenge me for a “duel” and listed all specific differences the math common core standards show comparing with the replaced standards, I would be able to demonstrate that those specifics are not really differences and will not influence learning outcomes of students. But let us assume for a moment I am wrong and CCS are very much different from the old ones. That would not make any difference because standards themselves are not important. What important is how states measure learning outcomes of students. And this part is absolutely up to states, especially now- after ESSA had been adopted by the Congresses and signed by the President.

If the content prescribed by the new standards is not much different from the content prescribed by the old ones, what was the point of spending millions?

The supporters of the CCS say, that the new standards provide a better structuring of the material and focusing on developing critical thinking skills. The latter statement is a wishful thinking (at best) because no one can reliably and on a large scale measure such skills.

Better structuring of a material means using a different language for describing the same knowledge and skills. It makes some difference for researches – they can claim a novel way for describing math. But it does not make much difference for teachers and – by the transitive property – to students. Teachers still have to teach basically the same content.

And finally, standards do not measure learning outcomes. Hence, even having the same standards states and districts can use absolutely incomparable measuring procedures – exactly as they have done it for decades before.

Some people say, the key word in “CCS” is “common”. Finally, the states will have a common ground to promote and assess education.

Firstly – again – the standards do not measure the learning outcomes (see above).

And secondly – there is no need for spending hundreds of millions of dollars for having a common math standard. Since all current math standards are essentially the same, the governors could have just taken 50 pieces of paper, write on each the name of a state, put them all in a hat, shake the hat, and pull one piece out. Done.

So, why have hundreds of millions of dollars been spent to achieve almost nothing (in terms of improving learning outcomes of student on a large scale; there are many collateral achievements, though, like tighter interstate cooperation)?

The shortest answer is: the force of habit.

Problem?

Let's pour money on it. Let's splash money around, some of it will stick to a right person at a right time.

However, the picture is a little bit more complicated. In reality there had been only a handful number of billionaires pushing for CCS. This article tells a full story of a rise and fall of CCS: http://fortune.com/common-core-standards/

Thank you for your attention.

© Valentin Voroshilov

P.S. I used to teach Physics at a small for-profit college. My students were smart and hardworking, but 99 % of them had serious problems with simple Arithmetic, and even more serious problems with Algebra. The only reason for that is that my students were taught in a wrong way (so, I had to re-teach them). When I read a publication on how to improve education, I see the huge gap between what researchers are talking about and the every day needs of teachers. It seems to me that the vast part of money spent on research in education does not really help teachers to teach better.

P.P.S. There is The Theory of Multiple Intelligences, which is becoming more and more popular among educators. One of the reasons for the growing popularity of the theory is the interpretation which sounds like “You can’t think? Relax, you can run pretty fast”. This approach implies that a poor teacher has a good excuse for the poor teaching job done in a class. It is a huge trivialization of the fact that human beings are capable of solving complicated problems in different fields including sport, music, design, art etc. But the fact that a person likes to dance more than anything else and can do it better than anything else does not mean that the person cannot or does not have to learn the multiplication table. The only reason that a good sportsman does not know basic Algebra (if it happens) is the poor performance of the Math teacher (who in this case has to be responsible for the intellectual damage done to the student by the poor teaching work). There is a definition of “a good physical health” and if a doctor has some damage done to the physical health of a patient, the doctor gets punished very hard. It is a time to define “a good intellectual health” and to start worry about intellectual health of the Nation.

P.P.P.S. Personally, I think that the most effective tool/environment for reforming the system is an On-Line Open Public School (at least a high school). The School has to be the combination of Internet, TV and in-paper teaching instruments. Anyone (at least potentially, as “a horizon”) should be able to get an education from a scratch to the level enough to pass SAT-I (at least). Focusing the efforts on that kind of a goal gives us - as the outcome - a logically and technologically connected grade-to-grade sequence of educational instruments.

P.P.P.P.S. There is a reason why politicians are suspicious to the role teachers might play in the reform. Teachers are conservative by the nature of their job (the subject they teach has not changed much over long periods of time). Hence, the Government turns to researches: “Dear professors, please, tell us what do we need to do to teachers to make them teach better?”. I would not say that this approach is working. The Government’s job should be making teachers to want to grow but still feel safe, making teachers to want to demand from researchers new good teaching tools and providing financial support for that. The hardest, the most important, and the most promising job of the Government is creating the system in which a teacher would be constantly motivated for a continuous improvement of the results of his or her work.

P.P.P.P.P.S. “Be careful what you wish for, it might actual happen”. President Obama wants that every high school graduate could get into a college and get a degree. The fastest way to achieve this goal is to accept into any college anyone who wants to enter and to print out a diploma for anyone who asks – done. Naturally, a lot of money would have been spent to promote and realize this approach. But would the result be the one he wants? Of course not. What he really wants is having everyone to have the high level of knowledge and skills. Let’s say one more time: “the high level of knowledge and skills”. Without having a tool to measure the desired level this goal is unachievable. And even more importantly, until the most of high school graduates have the knowledge and skills, which allow them to succeed in a college, there is no much sense to talk about college education at all (except its economics).

P.P.P.P.P.P.S I worked at a college, which had accreditation but accepted students who could not solve a simple 8th-grade math problem. Since then I do not trust the current accreditation system any more.

<<back to publications<< …...................>> to Teach0logy.xyz>>